The Encyclopedia Trap: Why Your Patient Needs a Thinker, Not a Hard Drive

I remember a second-year student—let’s call her Sarah—standing at a nurses' station in a bustling London teaching hospital. She was shaking. She had just failed a simulation assessment. It wasn't because she didn't know the material. If you asked Sarah the normal range for potassium or the side effects of Furosemide, she could recite them faster than you could type them into Google. She was a walking textbook.

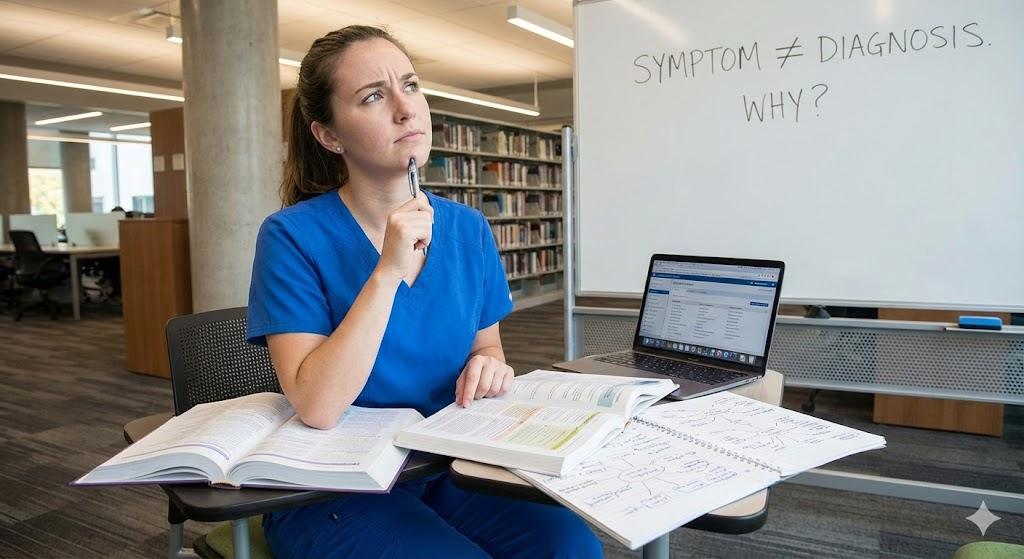

But when the "patient" (a high-fidelity mannequin) started showing signs of subtle deterioration that didn't match the classic textbook presentation, she froze. She kept trying to fit the patient's symptoms into the rigid boxes she had memorized. She was looking for a definition, but the patient was offering a puzzle.

This is the crisis facing nursing students today. You are drowning in content. Anatomy, pharmacology, ethics, law—the sheer volume of information feels like trying to drink from a fire hose. It is tempting, almost instinctive, to cope by memorizing facts. Flashcards become your security blanket. But here is the hard truth I’ve learned from fifteen years of reading essays and mentoring stressed students: Memorisation will get you through the exam, but it won’t get you through the night shift.

Breaking Free from the "SatNav" Mentality

Let’s be honest. We carry the sum of human knowledge in our scrub pockets. If I need to know the dosage of a drug, I can look it up in ten seconds. We don't need nurses who act as data repositories. We need nurses who act as processors.

Think of clinical reasoning like driving a car.

Memorisation is like using a SatNav (GPS). It gives you turn-by-turn instructions: "Turn left at the junction." If you follow it blindly, you might get to your destination. But what happens when there is a pothole the satellite didn't see? What happens when a child runs into the road? The SatNav doesn't care. It just says, "Turn left."

Critical thinking is looking through the windshield. It is understanding that while the map says "go," the environment says "stop."

In your academic work, I see this "SatNav" approach constantly. Students write essays that are descriptive lists. They list the symptoms of sepsis. They list the nursing interventions. They follow the map. But they fail to explain why the blood pressure drops as the infection spreads, or why fluid resuscitation takes precedence over antibiotics in that specific ten-minute window. They describe the "what," but they miss the "so what?"

Escaping the Description Trap in Your Essays

When you sit down to write your next assignment, you might feel the urge to "dump" knowledge. You want to prove to the marker that you read the book. Resist that urge.

High marks in UK nursing programmes are reserved for students who demonstrate synthesis. This means taking two separate facts and creating a third, new understanding.

How do you do this? You need to shift from being a reporter to being an investigator.

-

Don't just state the protocol; critique it. instead of writing, "Nurses should check vital signs every four hours," ask, "Is four hours sufficient for a patient with fluctuating consciousness? What are the risks of sticking to a rigid schedule here?"

-

Connect the physiology to the sociology. A patient isn't just a biological system failing; they are a person in a context. If a diabetic patient keeps returning with ketoacidosis, rote learning says "educate them on insulin." Critical thinking asks, "Can they afford the healthy food required to manage this? Do they have a refrigerator to store the insulin?"

This level of analysis is exhausting. I know. It requires mental gymnastics that can leave you staring at a blinking cursor for hours. It is the number one reason students burn out during dissertation season. You are trying to bridge the gap between theory and the messy reality of the ward.

Sometimes, you need a bridge. There is no shame in admitting that the transition from descriptive writing to critical argumentation is difficult. I often advise students that if they are stuck in a cycle of writer's block, getting a second pair of eyes on their work can be the difference between a pass and a distinction. Professional guidance, like the kind found at nursing assignment help, can help you structure these complex arguments, ensuring you aren't just listing facts but actually building a case. It’s about learning the structure of critical thought, not just buying a grade.

Surviving the Ward Round (Without Looking Foolish)

Critical thinking isn't just for essays. It is your shield on the ward.

Senior consultants and matrons have a way of sensing fear. They ask questions that seem impossible. "Why did you withhold the digoxin?" If your answer is "Because the textbook says so," you have lost them.

You need to cultivate a mindset of "Professional Skepticism." This doesn't mean being cynical; it means verifying.

-

Look for the Outlier: When you take a handover, don't just nod. Listen for the thing that doesn't fit. If a patient is post-op day three and "fine," but their heart rate has crept up from 72 to 94 over two shifts, that is your red flag. Memorisation ignores the 94 because it is still "within normal limits." Critical thinking worries about the trend.

-

The "Five Whys" Technique: This is a classic root-cause analysis tool. When you see a problem, ask "why" five times.

-

The patient fell. Why?

-

They slipped on urine. Why?

-

They were trying to get to the toilet unassisted. Why?

-

-

The call bell was out of reach.* Suddenly, the problem isn't a "clumsy patient"; it's a failure of environment and safety checks.

-

-

-

Challenge Your Own Biases: We all have them. If a patient is labeled "difficult" or "drug-seeking" in the notes, your brain naturally filters their complaints through that lens. Critical thinking requires you to actively strip away those labels. Ask yourself: "If this was my grandmother, would I interpret this pain differently?"

The emotional Weight of Thinking

There is a reason why rote learning is popular: it is safe. It is comfortable. If you follow the protocol and the patient dies, you can say, "I followed the rules."

Critical thinking is risky. It requires you to stick your neck out. It requires you to say to a senior doctor, "I am not comfortable administering this dose because..." It requires you to advocate when everyone else is tired and just wants to go home.

But here is the reality of the profession you have chosen: You are the final safety net.

Doctors prescribe, pharmacists dispense, but nurses administer. You are the last line of defence between a patient and a potential error. If you are on autopilot, relying on memorized lists, holes will appear in that net.

The Shift Begins Now

You might be reading this thinking, "I'm just a student. I don't know enough yet to think critically."

That is a lie.

You have intuition. You have eyes. You have a brain that is capable of complex problem-solving. Start small. In your next lecture, don't just write down what the lecturer says. Write down a question about it. In your next essay, don't just describe the pathophysiology; explain the consequence of it on the patient's daily life.

The transition from a student who memorizes to a nurse who thinks is the most painful part of your education. It is where the stress peaks. It is where the self-doubt creeps in. But it is also the moment you actually become a nurse.

Anyone can wear scrubs. Anyone can learn to take a blood pressure reading. But can you look at a set of vital signs and see the story they are telling you? The patient in Bed 4 isn't waiting for a textbook. She is waiting for you.