Why Your University Essays Keep Getting 2:2s (And How to Push into a First)

The notification pops up on your phone. Grades are released. You take a breath, log into the portal, and scroll down.

There it is again: 58%. Or maybe a 62%. A solid 2:2, perhaps scraping a low 2:1.

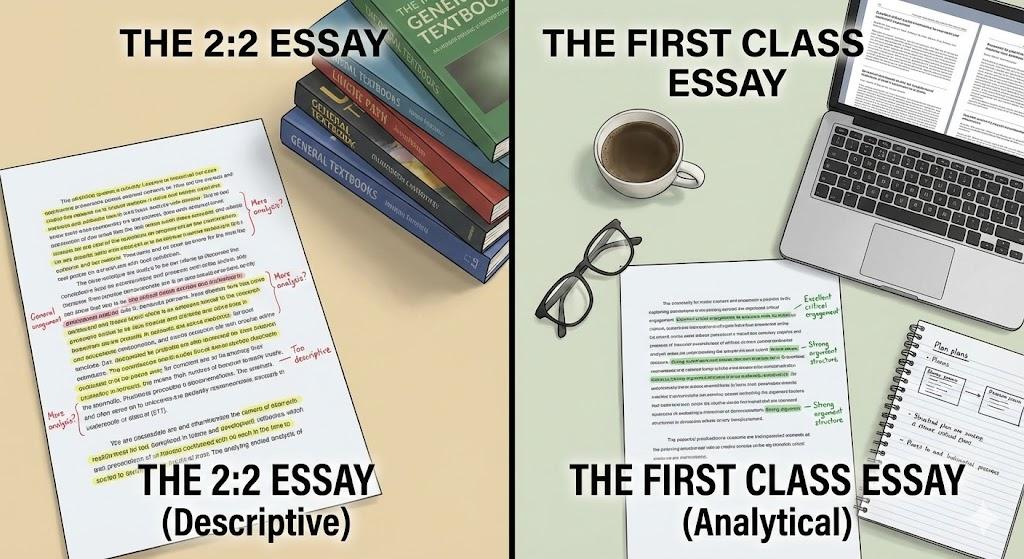

It is frustrating. You did the reading. You attended the lectures. You spent three nights in the library typing until your eyes blurred. Yet, the feedback is always the same vague comments: "More critical analysis needed," or "Too descriptive."

I have seen this frustration on the faces of hundreds of students over my 15 years in academia. You are working hard, but you are not seeing the results. Here is the uncomfortable truth I tell students in my office: University writing is not about showing what you know. It is about arguing what you think.

Many students are still writing excellent A-Level essays. At school, you get marks for gathering facts and presenting them neatly. At university, especially in subjects like History, English, Sociology, or Politics, facts are just the starting ingredients. The marks are in the cooking.

If you are stuck on that 2:2 plateau, you are likely falling into one of these five common traps.

1. The "Wiki-Dump" (Description vs. Analysis)

This is the single biggest reason essays fail to reach a First class standard. I call it the "Wiki-Dump."

You read five books on a topic, and your essay becomes a summary of everything you found. Paragraph one says what Author A thinks. Paragraph two says what Author B thinks. It is factual, it is accurate, and it is boring.

A tutor does not want to read a summary of a book they set on the reading list. They read it twenty years ago. They want to know what you make of it.

The Solution: Stop asking "What happened?" and start asking "So what?" Every time you make a factual statement, follow it up with analysis. Why does this matter? Does it support your argument, or complicate it?

-

Descriptive: "Marx argued that capitalism creates class conflict." (Fine, but basic).

-

Analytical: "While Marx’s view on class conflict is foundational, his focus on industrial economics means his theories struggle to explain modern, service-based economies." (Better. You are engaging with the idea, not just repeating it).

2. The "Kitchen Sink" Introduction

Your introduction is the handshake at the start of an interview. If it is weak and sweaty, you have already lost the room.

Many students start way too broad. If your essay title is about the causes of WWI, do not start with, "Since the dawn of conflict, mankind has fought wars." It is filler. It tells the marker nothing.

Often, students also fail to define the scope. They try to cover everything in 2,000 words and end up covering nothing in depth.

The Solution: Get to the point. Your introduction needs three things quickly:

-

Context: Briefly set the scene (narrowly).

-

Thesis Statement: One clear sentence stating exactly what your argument is.

-

Roadmap: Briefly tell the reader how you will prove it (e.g., "This essay will first examine X, before contrasting it with Y...").

3. Invisible Signposting

Imagine trying to drive through a new city without a sat-nav or road signs. You would get frustrated quickly. That is how a tutor feels reading an essay with no signposting.

Students often jump from one paragraph to another with no connection. One paragraph talks about economic factors, the next suddenly switches to political ideology. The reader is left thinking, "Wait, how did we get here?"

A good essay flows logically. Each paragraph should build on the one before it.

The Solution: Use topic sentences and transitionary phrases. The first sentence of every paragraph should signal to the reader what that paragraph is about and how it connects to your main argument.

Don't just say "Another factor was..." Instead, try connecting it: "While economic factors were crucial in the short term, the underlying political ideology provided the long-term justification for..."

4. Relying on the "Low-Hanging Fruit" Sources

You have a reading list. The lecturer starred two essential textbooks. You read those chapters, maybe glance at the lecture slides, and write your essay based solely on that.

You will pass. You might even get a high 2:2. But you won't get a First.

Tutors know exactly what is in the core textbooks. If your essay just recycles the main lecture points, it shows you haven't engaged deeply with the subject. It signals a lack of independent research.

The Solution: You must go beyond the essential reading. Use the bibliography in the textbooks to find specific journal articles. Journal articles are where the real academic debates happen. Using them shows you are engaging with current scholarship, not just introductory summaries.

5. Ignoring the Elephant in the Room (Counter-Arguments)

You have a strong argument. You spend 2,500 words proving you are right. You ignore anything that suggests you might be wrong because you fear it weakens your case.

This is a mistake. A First-class essay doesn't hide from opposing views; it invites them in and dismantles them. If you only present one side, your argument looks fragile.

The Solution: Dedicating space to counter-arguments shows confidence. "It could be argued by historians like [Name] that X was the primary cause. However, this perspective overlooks the crucial role of Y, because..."

By acknowledging the other side and explaining why your argument holds up against it, you make your position much stronger.

The Role of Academic Guidance in Writing

The jump from school to university writing is huge, and universities often assume you will just "pick it up" as you go. But academic writing is a specific craft with its own unwritten rules.

When you have been staring at the same draft for three days, you lose the ability to see its flaws. Your brain fills in the gaps in your logic because you know what you meant to say.

This is why many students benefit from external support. Getting a fresh perspective can be invaluable. A specialist can look at your structure, your signposting, and the depth of your analysis without the bias of having written it. Services like English essay writing help provide this kind of structural guidance. They help you see where your argument is getting lost or where your analysis is turning back into description.

Conclusion

Moving from a 2:2 to a First isn't about being smarter or writing longer words. It is about understanding the game. It is about shifting from being a passive collector of facts to an active critic of ideas.

By tightening your structure, deepening your analysis, and bravely engaging with counter-arguments, you can transform a mediocre essay into a piece of distinction-level work. Writing is a skill, and like any skill, it can be mastered with practice and the right approach.